Q. What do hydra polyps, mice and Columbia University neuroscientist Rafael Yuste have in common?

A. The Tällberg Foundation

Rafa, a 2018 Winner of the Tällberg/Eliasson Global Leadership Prize, is one of the most accomplished neuroscientists in the world, whose pioneering work and leadership helped launch what has evolved into the global BRAIN initiative. His lab at Columbia University uses hydras (tiny, fresh water polyps that are more or less immortal and have neurons spread throughout their bodies) and mice to explore how brains—most importantly, the human brain—work.

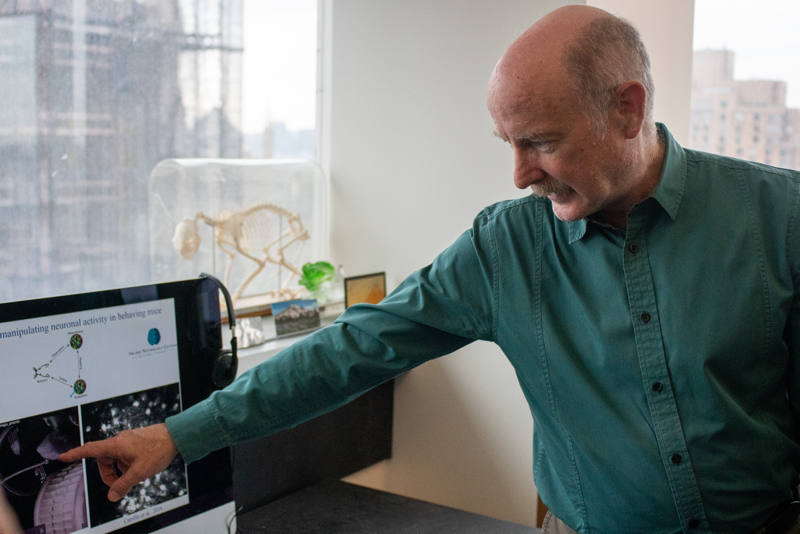

Rafael Yuste talking to the group in his lab at Columbia University (from left: Rafael Yuste, Alan Stoga, Cristina Gil, Mark Mitton, Terrence Checki, Robin Wood Sailer, Miguel Angel Moratinos, Alejandro Santo Domingo

On Friday, January 30, Rafa hosted a group from the Tällberg Foundation for a tour of his lab, a presentation of key aspects of his research, and a discussion of the profound ethical implications of the current explosion of knowledge about the brain.

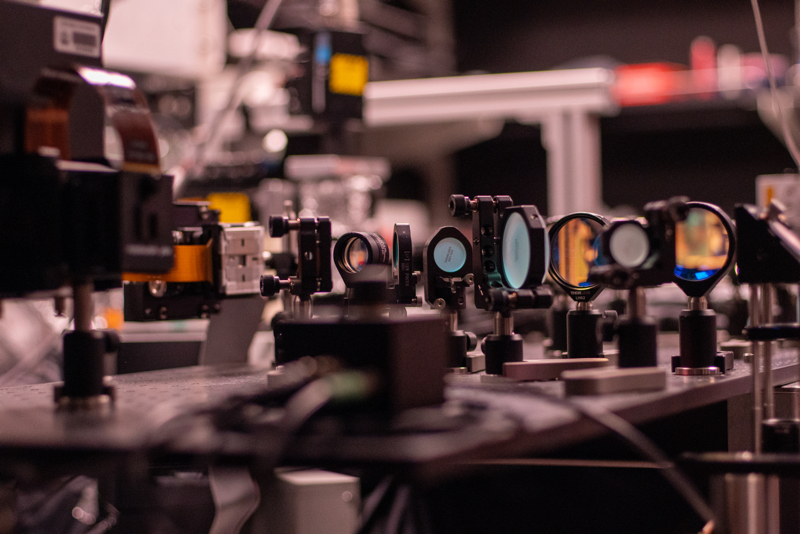

“Our goal is to understand the nature of a thought,” Rafa explained. And he and his colleagues are doing that by developing new tools to monitor neural activity intended to show how individual cells and complex neural circuits interact in both time and space. It’s that interaction, he said, that is the physical manifestation of a thought: “when neurons light up at the same moment.”

The Tällberg participants saw a movie of an experiment that demonstrated some of what is known and still unknown. A mouse was secured to a headrest, with a water tube and a video screen in front of it. The mouse had been trained to lick or not lick the water tube when it saw particular patterns on the screen. As it observed and reacted to the patterns, a sophisticated optical microscope recorded the functioning of the mouse’s brain. Different neurons were activated when the mouse licked and when it did not; the scientists were able to identify the exact patterns of the neural firings.

That work was amazing enough, but the real WOW! moment came next. Based on the patterns that had been identified, the scientists then used an optical tool—essentially light—to stimulate the mouse’s brain in ways that caused the mouse to lick or not to lick, depending on the sequence they activated.

In other words, the researchers were able to create a thought inside the mouse’s brain in a non-invasive way—a thought that was not the consequence of input from the animal’s senses. And, Rafa told us, “If we can do this with a mouse, it can likely be done with a human, since the brains are essentially the same, but different in size.”

Based on that work, one of Rafa’s colleagues is developing an experiment involving decision. Can the scientists identify thought patterns when the mouse makes a choice? If so, can they replicate the pattern optically, and induce the mouse to make a particular choice?

Rafael Yuste, a 2018 Winner of the Tällberg/Eliasson Global Leadership Prize

As scientists improve their understanding of the brain, they are looking for tools to facilitate brain to computer interface (BCI). Ken Shepard is a Professor of Electrical Engineering and of Biomedical Engineering at Columbia who is developing a small, flexible chip that ultimately could be inserted into a human brain to allow direct communication between the brain and a computer. He displayed a state of the art, pliable, ultra thin chip that is only 1.5 centimeters square but hosts 65,000 electrodes, an antenna and a wireless power source—essentially a tiny, implantable Wi-Fi device for two way transmission of massive amounts of data.

“We want to use this device as an interface with the visual cortex, first of a monkey’s brain and, ultimately, of a human’s brain” explained Ken. “It could become a visual prosthetic for people who have had traumatic injury to their optic nerve.”

In other words, one possible application of this technology could be the miracle of restoring sight to someone who lost it. But there are others at least as profound. On the one hand better understanding of how the brain works could allow for treatment of diseases ranging from schizophrenia to Parkinson’s. On the other hand, the ability to manipulate human behavior through invasive or non-invasive interventions could be abused in ways that movies like “The Matrix” or “Inception” only hinted at.

That risk has led Rafa and a group of other neuroscientists to launch The NeuroRights Initiative to protect neural rights as human rights and to promote ethical leadership in the fields of neurotechnology and artificial intelligence. On the one hand, the scientists have been working with Chile’s political leadership to write such protections into the country’s constitution; on the other, they are drafting a “technocratic oath” for entrepreneurs, physicians, and researchers that would be similar to the Hippocratic Oath pledge to uphold specific ethical standards.

Indeed, it was Rafa’s leadership in this arena that persuaded the jury to award him his Tällberg/Eliasson Global Leadership Prize.

“Rafa challenged us, as individuals and as part of the Tällberg network, to action,” said Alan Stoga, chairman. “In a well functioning global society, this kind of issue would easily attract the support of leaders and citizens everywhere. But today the risk is that the breakthroughs that scientists are making in understanding how the brain works could be weaponized by nations, monetized by corporations or abused by rogue actors. We need to respond to Rafa’s challenge with the urgency and imagination it demands.”

The meeting at Rafa Yuste’s lab is one of a series of conversations designed to offer Tällberg SNF Fellows unique insights into the policy issues and challenges that define the 21st century.